Comments to the MBIE Building Performance Practice Advisory 11 “Grade 500E reinforcing steel – good practice”

Introduction

This HERA Guide provides updated technical guidance on the welding of reinforcing steel to assist users of Practice Advisory 11: Grade 500E reinforcing steel – good practice (2nd edition, 2016), issued by the New Zealand Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE). It clarifies aspects of the welding recommendations in that document particularly with regard to shop and site welding, “tack” welds, and “non-load bearing welds”.

The intended audience includes structural engineers, designers, building consent authorities, welding supervisors, inspectors, and builders.

This Guide references AS/NZS 1554 “Structural steel welding – Part 3: Welding of reinforcing steel” as the key requirement for all welding, and confines itself to the micro-alloyed (MA) grades of bar.

Grade 500E Reinforcing Steel

Although Grade 500E reinforcing steel has been in use for many years, its weldability remains a source of uncertainty for some users. HERA frequently receives queries on whether this grade can be reliably welded, the role of tack welds, and its suitability in seismic applications.

HERA has substantial experience in welding rebar. When the E grades were introduced in the early 2000s, HERA, in conjunction with Pacific Steel, conducted extensive testing to demonstrate how welding procedures to AS/NZS 1554.3 can be qualified. Testing encompassed the full range of bar diameters and all prequalified joints. All specimens were visually inspected and mechanically tested, confirming that acceptable mechanical properties are achievable when the Standard is followed.

Tack Welding

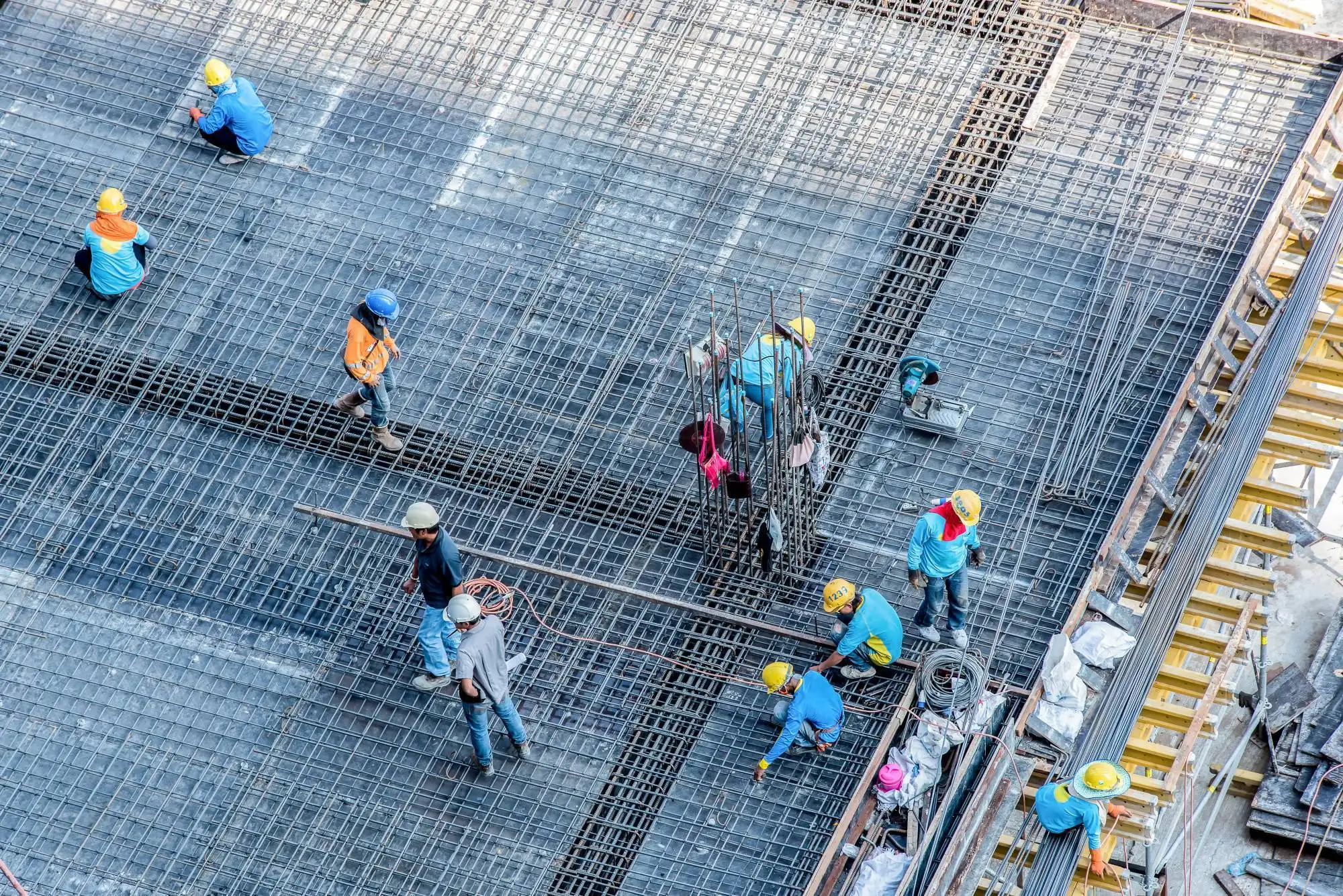

Welding is commonly used in the assembling of rebar into components such as pile cages. These welds are not intended to provide structural strength in the completed structure but rather to hold the rebar in position during handling, lifting, and concreting.

To avoid confusion, terminology from AS/NZS 1554.3 should be consistently used. Misusing the term “tack welding” when referring to what are technically “non-loadbearing” or “locational welds” leads to misunderstanding.

A tack weld is a small weld made to hold components in alignment before completing the final weld. They are typically incorporated into the final weld or removed prior to completion. When properly executed, the resulting final weld—including any incorporated tack welds—will meet the quality requirements of the Standard.

Issues arise when tack welds are improperly applied or substituted for non-loadbearing joints. Poorly formed tack welds often exhibit defects such as porosity or shrinkage cracks and may cause localised hardening and cracking. These welds typically lack ductility and load-bearing capacity.

However, tack welds remain useful and are necessary in certain situations, such as direct butt splices. When carried out in accordance with Section 5.6 of the Standard and properly integrated into the final weld, they are both permissible and effective.

Non-Loadbearing Welded Joints and Locational Welds

Non-loadbearing welded joints are those not relied upon in the structural design of the reinforced concrete. Their purpose is to maintain rebar alignment during transport, handling, and erection. These are also known as locational welds.

Although termed “non-loadbearing”, these welds must possess sufficient capacity to withstand handling stresses. The requirements for such welds—including size, length, and location—are detailed in Section 3.3 of AS/NZS 1554.3.

These welds must be executed to a qualified welding procedure and not left to the welder’s discretion. Cross-joints, the most common type, are not prequalified and must undergo shear testing for welding procedure qualification.

Designers and detailers of assemblies using non-loadbearing welds need to take into account the requirements of Section 3.3 e.g. weld details need to be on drawings or other documents, and safe lifting points must be clearly marked on welded assemblies.

Shop vs Site Welding

PA11 rightly advocates for shop welding, but offers limited guidance for circumstances requiring site welding.

As shop welding provides a well-controlled fabrication environment it is always preferred for any form of structural welding. There are situations however where site welding is the only option. Challenges for site welding include exposure to the weather, access to the joint for the welder, the presence of moisture, dirt, concrete and the like, and safety. Provided these factors are understood and addressed by those managing a site, competent welders can be expected to produce site welds to the required quality level.

Roles and Responsibilities

Successful rebar welding requires coordinated involvement from designers, welding supervisors, welders, and inspectors.

– Designers need to be aware that under earthquake loading some types of joints may not meet seismic design requirements. For example, lap joints, especially with a weld on only one side will rotate under high loads, and fillet welds on T-joints (bar to plate) need to be specifically assessed. This especially applies to repair work or the modification of existing structures where there can be limited access for the welder to all sides of the joint.

Requiring welding procedure approval by the designer (or their e.g. welding inspector) before work starts is a low-cost precaution to ensure site welds are both practical under site conditions and suitable for earthquake loads.

– Fabricators and welding supervisors must understand the differences between welding structural steel (AS/NZS 1554.1) and reinforcing steel (AS/NZS 1554.3). A current copy of Part 3 must be available and understood.

– As the welding inspector’s role usually involves interaction with both designers and welders, they need at least a basic understanding of potential design issues and the practical aspects of rebar welding. Obviously access to copy of the Standard is essential, and how rebar welds are sized and measured.

Summary

Grade 300E and Grade 500E MA reinforcing bars are readily weldable and will achieve the required mechanical properties when welded in accordance with AS/NZS 1554.3.

Key takeaways:

– “Tack” welds should not be confused with “non-loadbearing” welds. Tack welds have their uses, but they are not a substitute for non-loadbearing (or locational) welds.

– All welding must be performed to qualified and documented procedures.

– Site welding is acceptable when properly managed.

– Under seismic loading, certain joint types may perform poorly:

– Lap joints (especially with single-sided welds) may rotate under stress.

– T-joints with fillet welds require specific evaluation.

– Designers must assess the seismic suitability of all welded joints, particularly in retrofit or repair work.

– All stakeholders must understand and fulfil their respective responsibilities.

References

- AS/NZS 1554.3:2014 – Structural steel welding – Welding of reinforcing steel

- NZS 3101:2006 – Concrete Structures Standard

- NZS 3109:1997 – Concrete Construction

- AS/NZS 4671:2001 – Steel reinforcing materials

HERA remains available to support engineers, fabricators, and regulators with advice and technical resources on rebar welding. For further assistance, contact: welding@hera.org.nz